Becoming

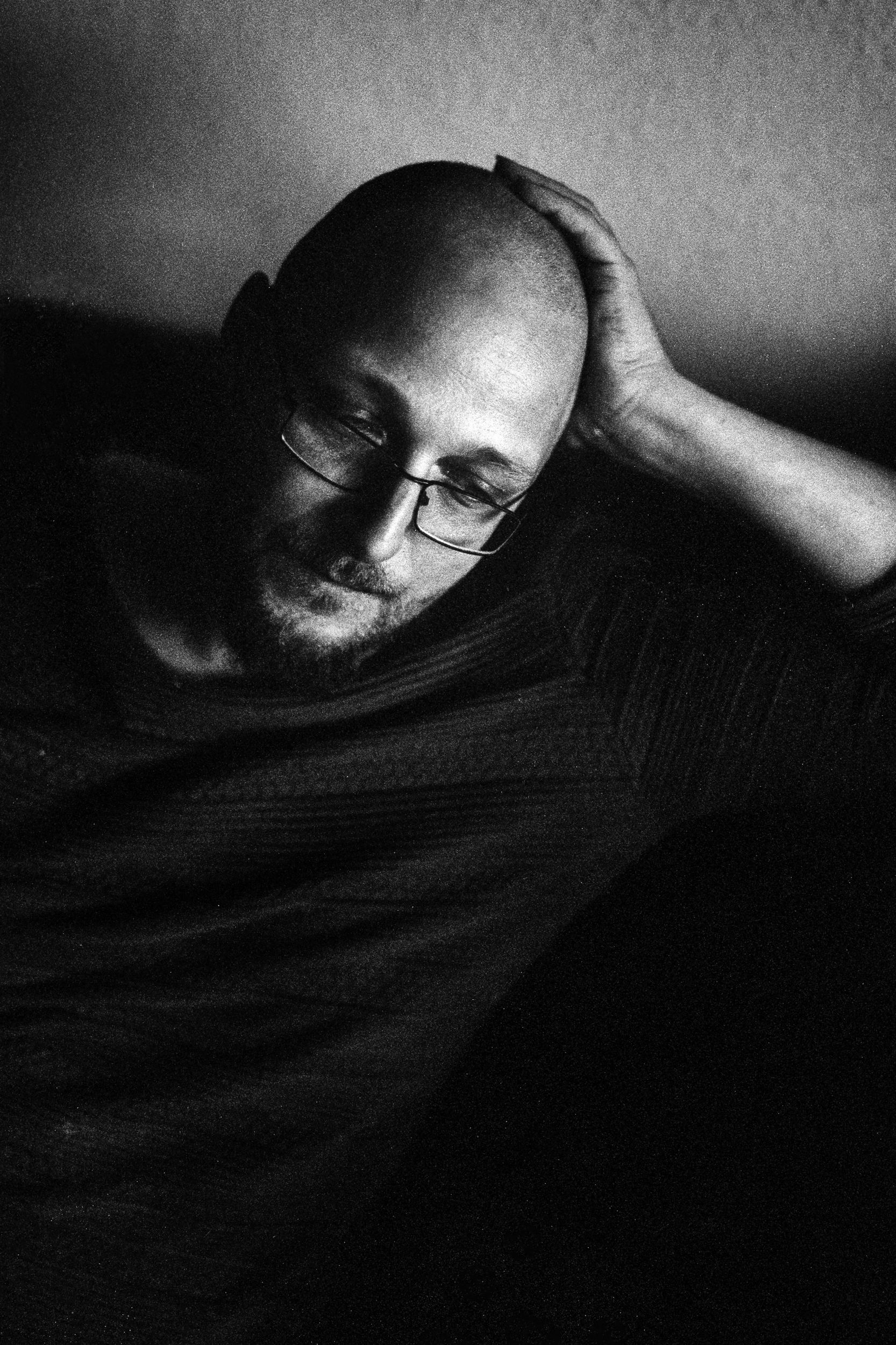

After years of searching for a place to sleep and getting in trouble with the law, Pino Paank is now living a life that suits him. The wounds have healed, but scars keep him aware of the past being real.

Next to a patinated red brick building in the former industrial harbor of Sydhavnen, a group of middle-aged women are glancing around as if they are a bit lost. The yellow door of the building is pushed open, and a man wearing a long, brown trench coat and bright red loose jeans with blue suspenders steps out. He opens his army green military-style shoulder bag and takes out a pack of rolling tobacco, papers, and filter tips. With a swift move, he rolls a cigarette. "Hello, my name is Pino, and I will be your guide today" the man introduces himself and nudges his cap a bit higher.

He reaches into his pocket for a lighter. Inhale, exhale, and a puff of smoke floats in the air. "I got evicted from my first apartment at the age of 18," Pino starts to unravel his life story. "A guy who wasn't a friend of mine thought it would be funny to start a fire in the middle of my living room. That was the start of my ten-year career as a couchsurfer."

Pino Paank, 34, is one of the dozen guides taking people around the city of Aarhus, Denmark, and showing them what the city looks like from the perspective of the socially vulnerable. They are called Poverty Walks. Today, a group of women working closely with refugees and immigrants get to hear Pino.

Pino lived his first years on a small island called Fanø in the southwest of Denmark. He was his parents’ first child. After they got separated, Pino stayed with his mother. "I only have a few memories of my biological parents living together,” he says.

The North Sea coast and island life got left behind when Pino and his mother moved to Djursland, the east of Denmark. His mother found a new man, and Pino got two step-sisters. The relationship eventually ended, and Aarhus called for the single-parent family when his mother started studying.

Pino wasn't the easiest teenager to handle for a single mom; he´s the first to admit that. At the age of 15, the situation escalated to the point that he was put into foster care. He talks with a sense of understanding about his mother's decision to seek help. "First, I was at boarding school and then was sent to a place for young troublemakers."

Pino wasn't the easiest teenager to handle for a single mom; he´s the first to admit that. At the age of 15, the situation escalated to the point that he was put into foster care. He talks with a sense of understanding about his mother's decision to seek help. "First, I was at boarding school and then was sent to a place for young troublemakers."

On the edge of adulthood, he got his first taste of the criminal justice system. While staying in an institution that deals with young offenders and teenagers who cannot stay at home, he punched one of the employees.

The sun hits the edges of the brick building and makes a sharp-lined shadow behind the women in Sydhavnen. Bicyclists and cars drive by, and Pino reminds the group to look out for the road hogs as he leads them toward the city center. Every now and then, a friend or acquaintance wawes at Pino, and they quickly change a couple of words. "Pino is the best guide," one of them shouts.

The walk continues into an alleyway behind the Aarhus police headquarters. The women gather around Pino as he puts out his cigarette with his fingers so he can light it up later. "I have had my fair share of clashes with the police and security guards," he starts.

His first conviction was at the age of 17, and two were still to come for fighting with the police. Three times in jail and over 60 times arrested. "I stopped counting after that." There is no pride nor too much regret in his voice. Things happened, and he took them as they came. A sense of bitterness can be read from how the authorities treat the socially vulnerable. "The police lack the understanding of how to deal with people living on the streets."

Pino started telling his story on guided tours just before the covid pandemic hit the world. Once a week, people from different social classes get to walk in his shoes for a couple of hours. They listen carefully when Pino talks about his former drug use, shoplifting, and thoughts on how we could better support the people on the outskirts of society. He received help when he least expected it; while serving his last sentence in jail.

A couple of seagulls scream and fly over the Aarhus river near a big department store. Pino leads the group through the crowd to a slightly calmer place and suggests that they can sit on the benches next to the canal. An elderly man stops to listen in on how you can couchsurf for almost a decade.

After getting evicted from his first apartment at 18, Pino had to find a roof over his head. Going back home to live with his mother wasn't an option, so he started sleeping on friends' and acquaintances' couches. He built a network around him to have a place to sleep but sometimes was forced to lay his hat under the sky.

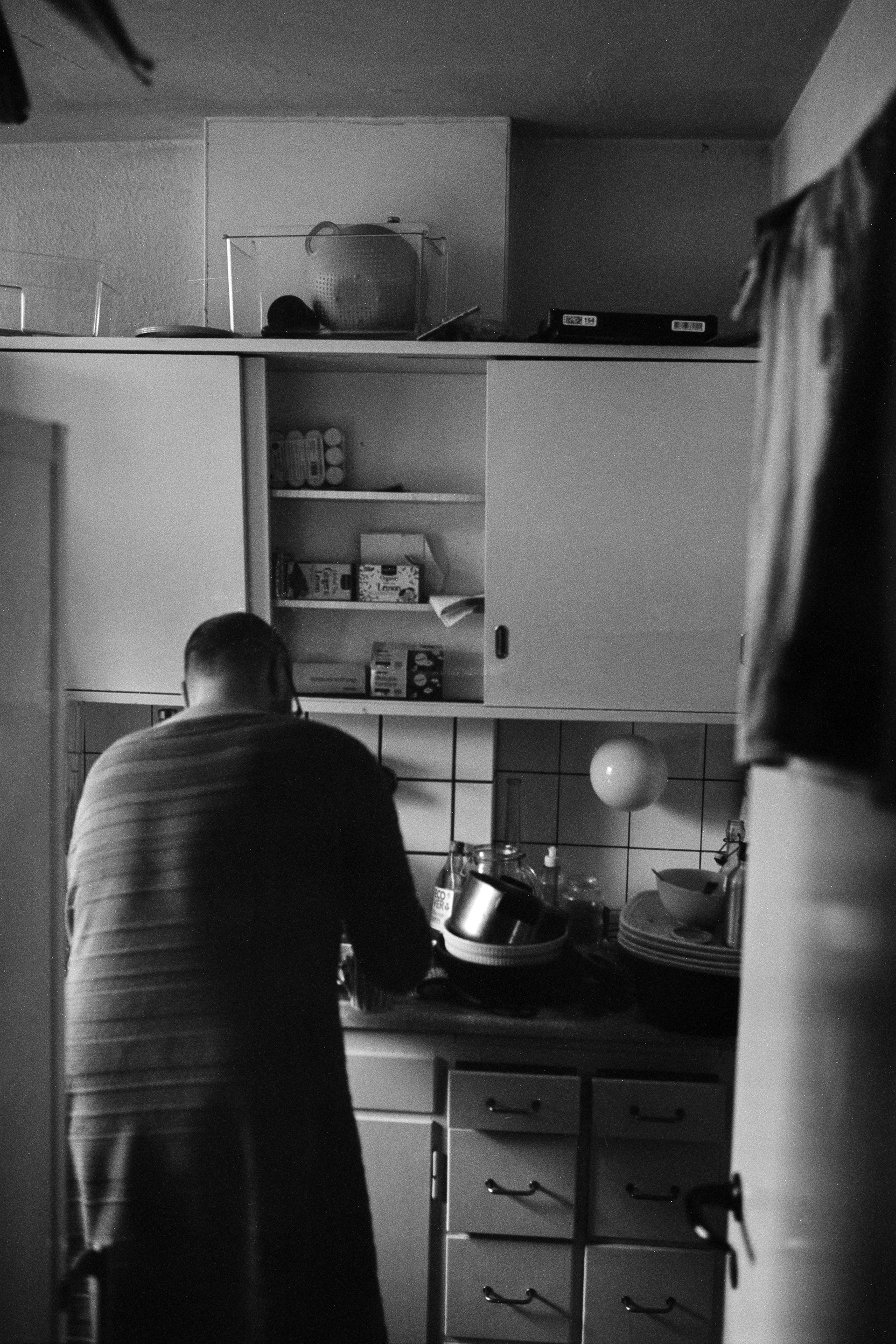

"It was a learning curve. I needed to make myself useful, clean a bit in the apartment, do the dishes, that sort of thing. And also stop being an asshole", Pino refers to his former self.

A typical couchsurfer's day is spent walking the long streets in the city, looking for a place to sleep the next night, and trying to stay out of trouble. And trouble usually finds you when you are trying to survive in the rain and cold, as Pino puts it.

After getting out of prison, Pino got a new beginning. In the midst of serving his sentence, he was offered an apartment. "I was angry at first because I counted on the system to fail me again, but this time it surprised me."

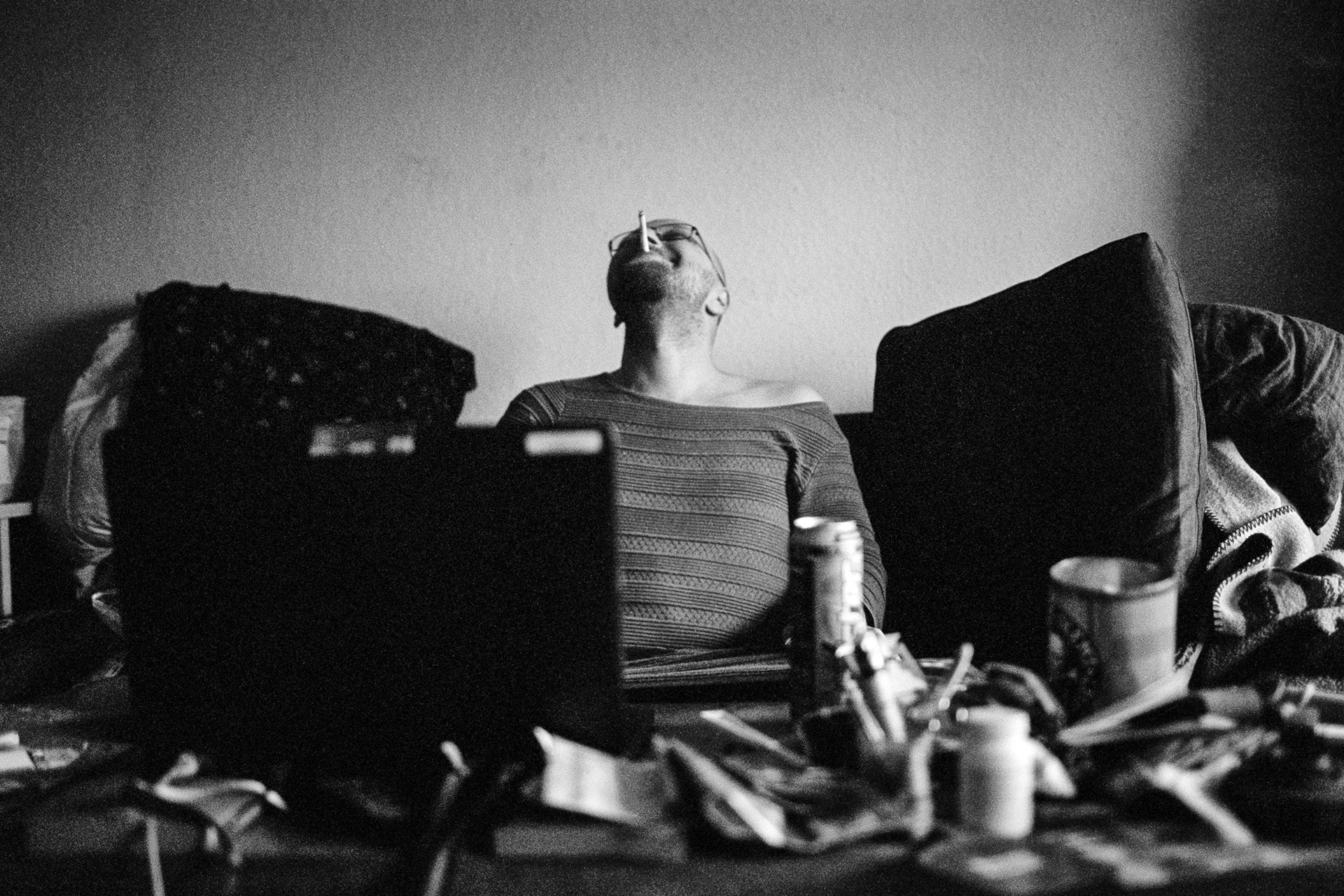

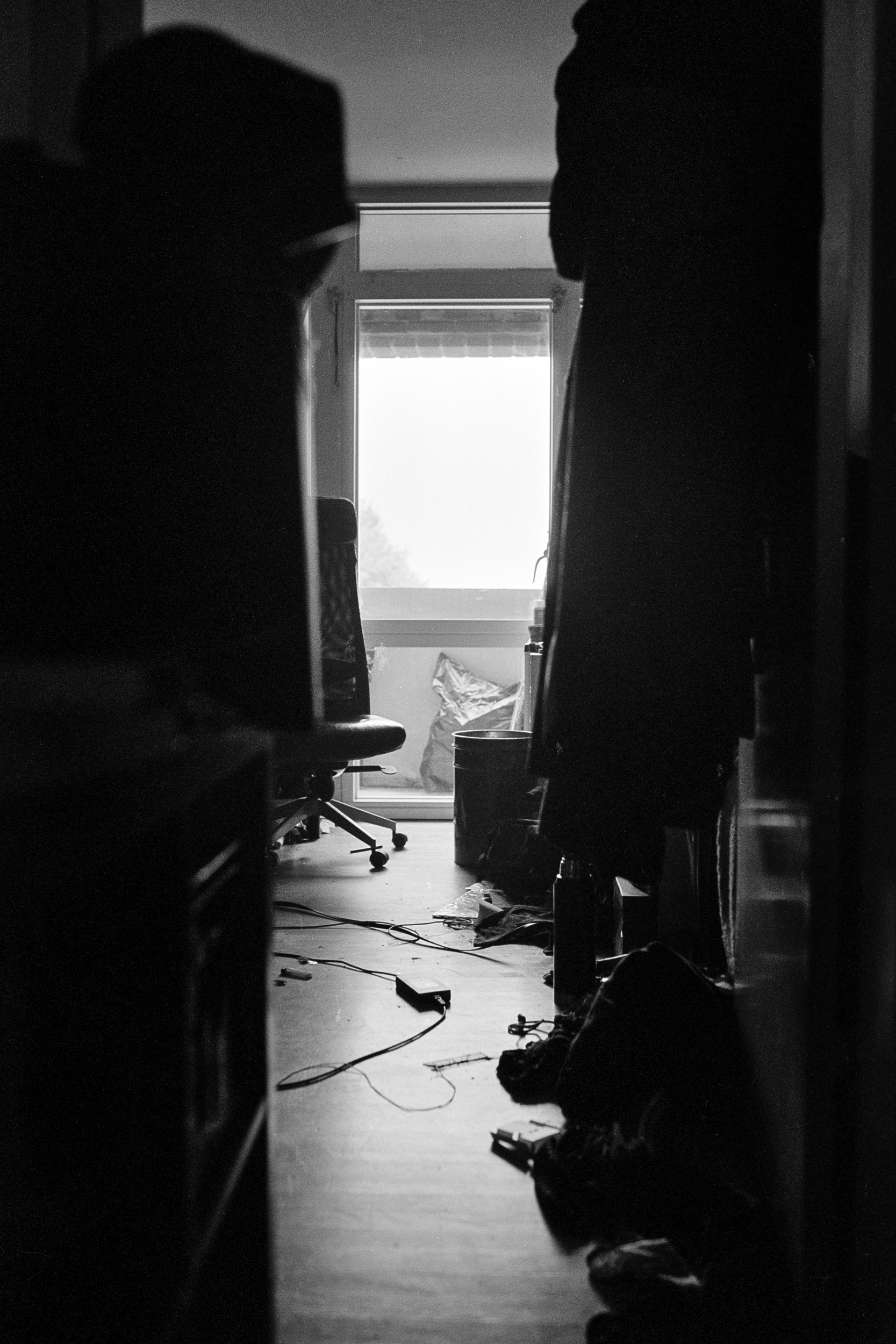

Living without a home for years leaves traces. Moving into a place of your own isn't smooth sailing from there on; it takes time to adjust to a new situation. Many go back to the old habits because that is all they know. Pino still found himself sometimes on other people's couches. "I couldn't be alone because I had been staying with someone for so long. I was still spending much time on the streets," he recalls.

After six years of living in a compact apartment close to the city centre, Pino feels privileged to actually have a place to call his own and invite people over. There are still things to learn and improve. First on the list is going through everything saved over the years and sorting the items on the bed, so he can finally sleep on it instead of the couch.

One person has been spending more time in Pino's apartment than others. While volunteering at Skraldecaféen, which helps people in financial need with free food, he met a Ukrainian refugee, Nadia. The couple has been seeing each other since June.

"We are still trying to figure each other out because of the slight cultural and language barrier. We communicate in English, but I teach her Danish every time we meet", he grins softly.

Getting an early retirement has eased the transition of getting back to an everyday life. The opportunity to work some hours without it cutting into his pension is appreciated. Alongside the guided tours, Pino has another job collecting bottles and cans with a deposit from private companies and sorting them. "I really like my life now," he says.

He stays in contact with his mother and step-sisters and dreams of paying his debt and buying a boat. The first plan is to sail the inner rivers of Germany.

The sun flares the Rainbow Panorama's colours from the rooftop of Art Museum Aros. Pino checks his mobile phone for the time as he leads the group to the last stop of the walk. "Now, it’s time for questions," he says when the group reaches Mølleparken.

Pino hopes that the one thing that people take with them from his walks is that the next time they meet socially vulnerable persons, they will treat them as human beings. "It really hurts when people look straight through you. Sometimes a smile is enough."

One hand raises, "Would you do anything differently if you had the chance?"

"Sure, I have some regrets and wish I hadn't hurt others on the way. I have apologized to some people. But I wouldn't do things differently. I went through all this to become who I am now", Pino says.